Circumnavigation, Interrupted

They’re mad as hell and they’re going to take it.

Sitting in the harbor at Malé, capital of the Maldives, once home to kings, the skipper of the Kelly Peterson 46 , Esprit, reports, “The country offers a $350 cruising package to visit the other islands, but we are going to sit right here with fifteen other boats that have decided not to do the crossing.”

The crossing that would take them through the thickest of pirate waters en route to the Red Sea, the Suez Canal, and the Med.

Instead, Esprit will ride a freighter to the Med, with plenty of company, come the end of March.

Jamie, Katie and Chay in Thailand, not so long ago. Photo sailingesprit.com

Jamie, Katie and Chay in Thailand, not so long ago. Photo sailingesprit.com

Five hundred miles into the pirated waters of the Arabian Sea they had ventured—feeling prepared, a man and a boy armed with guns in the cockpit and long knives at their belts, and a woman ready to pose as a man—with most of a circumnavigation behind them and happy visits to Sri Lanka and India still fresh in their minds. Then they learned that their cruising friends Scott and Jean Adam and two crew aboard the Davidson 58, Quest, had been killed. Brutally. By pirates. After departing India four days ahead of them.

Esprit had known as they left that Quest had been taken, but—

You have to take your chances, but—

The stakes had just escalated.

I believe we can consider the route through the Arabian Sea, past Somalia, now closed to all but the bold, not necessarily the wise. Dodging through and probably being okay no longer has a happy ring to it. Somali attacks are thickest off the coast of Oman (how ironic that the Sultanate of Oman has made a strong and welcome bid to join the ranks of mainstream yachting), but piracy is broadly spread across the entire region as far as the Maldives.

For circumnavigators, beating upwind around the Cape of Good Hope remains an option, but it seems that most of the boats now coming ’round from Asia, boats that had expected to transit the Suez Canal, are opting to ship their boats to the Med via freighter. “We’ll meet the ship in Turkey, in Marmaris,” said the skipper of Esprit. “We’ll take a week or two to explore that part of Turkey, then put the boat on the hard and go home to make enough money to cover the cost of shipping—which is more than the cost of a year of cruising.”

Might they ride along with the boat aboard Sevenstar Yacht Transport to Marmaris?

“One ship was taken a while ago while transporting yachts, so why would we want to? We’ll fly.”

I have this picture in my mind of Conestoga wagons creaking across the prairie toward Cheyenne country, families a’settin on wood planks, scouring the horizon . . .

We first met Esprit in this space as Chay, Katie and Jamie, with Katie declaring their coming of age as a voyaging team: “We are no longer the McWilliams family. We are Esprit.”

Personally, I met these folks outbound from San Diego, California on the 2003 Baja Ha-Ha Rally, and though we’ve kept in touch, I haven’t seen them since we arrived together in Cabo San Lucas, where I finished young Jamie’s lunch in a beachside café (wouldn’t happen today) and Katie mused, “There’s an air of unreality to this. I ask myself, have we really done our first thousand miles?”

The harbor at Malé is 26,000 wandering miles on from San Diego and the starting line of the Ha-Ha.

Along with the cruisers gathered in Malé to hitch a ride on a cargo vessel are all but one of the boats remaining in the Blue Water Rally, now in-harbor in Salalah on the southeastern coast of Oman, close to the border of Yemen. They left Gibraltar eighteen months ago. s/v Quest had been part of the Blue Water Rally, bound for Salalah when the pirates struck, so there is more than enough shock to go around. And, after conducting eight of these circumnavigations, safely herding fleets of mostly first-time long-distance sailors, Blue Water Rallies Ltd. has announced that it is going out of business, a victim of hard economic times, and piracy. Which perhaps are one and the same. Their statement assessing the moment: “Proceeding in any direction from Salalah is too high-risk for the majority of the participants.” The sailors had expected to complete the rally with celebrations in Crete, but the rally is effectively ended in Salalah. They’re going to Marmaris, and that’s that.

The harbor at Salalah . . .

The Blue Water Rally fleet at Salalah, Oman. Photo Blue Water Rallies Limited

The Blue Water Rally fleet at Salalah, Oman. Photo Blue Water Rallies Limited

(A few years ago, on assignment for SAIL Magazine, I cruised through Fiji with that year’s edition of the Blue Water Rally. The times seemed complicated enough at the time, but now we know, those were simpler times.)

Back to Esprit. They had harbored in Cochin, a mix of old and new—

Kochi International Marina, Cochin, India. Photo Blue Water Rallies

Kochi International Marina, Cochin, India. Photo Blue Water Rallies

Then, five hundred miles out of Cochin and eight hundred miles short of Salalah, Esprit learned of the fate of Quest, up ahead, and made the decision to turn around and pass again through waters that were risky, but less so than the waters beyond. In recent weeks a handful of boats have successfully reached the Red Sea. They include Imagine, Pegasus, Cyan, La Palapa and Convergence, the latter a cat-rigged Wylie ketch owned by the founder of West Marine, Randy Repass. But these new developments are going to change the game.

Chay advises that pirate attacks, mapped out, “cover almost the entire Arabian Sea as far south as Madagascar and the Gulf of Aden, even as far east as the Maldives and India. The Maldivian Coast Guard holds 39 pirate prisoners.”

Chay had sent ’round a missive headed, Giving Up the Dream, so over a Skype connection to Malé, I asked Chay about the disappointment level.

“Very high,”

Was the answer.

“Jamie is pretty angry at not being able to do the circumnavigation whole.”

The skipper of Imagine sailed to Oman with family, hugging the coast of Pakistan. But from the capital of Oman, Muscat, he put his family on a plane to fly out and continued on with new crew. (If nothing else, these people will have unique adventures to look back upon, though not of the sunset-with-a daiquiri variety.)

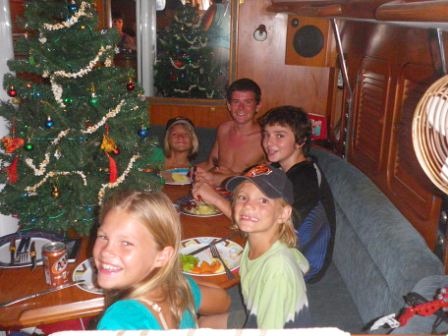

The prospects seemed happier in December, when cruiser kids from Imagine and Tin Soldier joined Esprit for Christmas dinner. Jamie and friends . . .

Grant (Imagine), Jamie (Esprit), Jaryd (Tin Soldier), and Noah and Caroline (Imagine) enjoying Christmas dinner aboard Esprit. Photo by sailingesprit.com

Grant (Imagine), Jamie (Esprit), Jaryd (Tin Soldier), and Noah and Caroline (Imagine) enjoying Christmas dinner aboard Esprit. Photo by sailingesprit.com

Jamie, btw, was three years old when mom and pop bought Esprit, six years old when I met him in Baja in 2003, with more of Mexico and all of the Pacific yet to come. Picturing Chay and now-teenage Jamie in the cockpit, each with a long knife at the belt and knowing where to reach for the shotgun, flare gun, spear gun, well, they’ve lived the dream, but that ain’t it.

At sailingesprit.com, Chay puts things this way:

“It used to be that we were very concerned about freighters when we were at sea. Because the freighters usually didn’t keep a good watch, we had to be worried about being run down. Now the watch is all about looking for pirates. The freighters keep an excellent watch and are worried when they see us (a small boat) because we might be a pirate. We used to not have a second thought about a fishing boat except for how to stay out of his nets. Now our first thought is, could that be a pirate mother ship.”

I repeat, Esprit left Cochin for Salalah knowing that Quest had been taken and yet willing to assume some risk for the sake of that guiding light, the circumnavigation. This was the general outlook in the cruising fleet. But updates advised Esprit to double previous estimates of a likely opponent’s strength:

“We received intelligence that the pirates were now using two skiffs instead of one and could place as many as 19 pirates on the attack. News reports were also stating that the pirates were torturing their hostages, something we had not previously heard about.”

And then:

“On February 23, 8:30 am, after fighting light head winds for four days and having realized that we had damaged our prop in Cochin [and could motor only at reduced speed] we heard the news of the deaths of our friends, Scott & Jean Adam, with whom we had cruised in Tonga and New Zealand.”

“At this point, we had the densest area of previous pirate attacks ahead. As a family, we made the difficult but important decision to turn around. There were reports of pirates on our path back to India, but the risks were less. Two days later the Danish s/v ING [ING had been a dockmate of Esprit while passing through Asia, with seven aboard including three teenagers] was pirated in the very position where we would have been, had we continued on course.”

“At this point, we had the densest area of previous pirate attacks ahead. As a family, we made the difficult but important decision to turn around. There were reports of pirates on our path back to India, but the risks were less. Two days later the Danish s/v ING [ING had been a dockmate of Esprit while passing through Asia, with seven aboard including three teenagers] was pirated in the very position where we would have been, had we continued on course.”

The crew of ING was still in captivity at last report.

Chay adds, “People used to ask, ‘Don’t you get scared?” Even one of the captains on a freighter we talked to in the Gulf of Bengal asked us this question. Our answer has always been ‘no.’ That has changed.”

Returning to Cochin and then moving on to the Maldives, they had their own full-alert hour, a false alarm as it turned out, but did I mention, full alert?

Esprit—the three-people component of Esprit, not the boat part—will all too soon be off to Boulder City, Nevada, to turn the lights back on at the small engineering company owned by Chay and Katie. Esprit faces the prospect of someday completing a circumnavigation-minus-1,500 miles. No one will hold the asterisk against them. But it becomes clear that a historically-brief, bright moment in long distance voyaging has darkened.

Esprit’s anti-piracy tip of the day: Greasing toe rails and lifelines will make it harder for someone to board your vessel.

Including yourself, later.

.