FutureSailing – Bob Johnson

Part Two of a series of conversations with people who are driving profound changes in the way that we are able to sail. Once the opportunities are clear, how will people choose to sail?

“My vision,” says Bob Johnson, “is a sailboat you turn on.

“Every once in a while I like to sit down and ask, what’s over the horizon, and how do we get there? Ultimately, it can be done. We can automate sailing.

“People wonder, why, when the joy of sailing is doing things? I get that. I like fast, stick-shift cars. But you’re always free to do as much as you want. I think we could bring in more people, and keep more people in sailing, if we simplify it.”

If you come from the racing side of sailing, you may not know Bob Johnson, founder and designer of the Island Packet line of cruisers. And if you know the boats you probably think of them as conservative. But.

An Island Packet today is a different beast from the Island Packets of 15 years ago, much less the boats of 1979, when Johnson founded the business to do the thing he had always wanted to do. At that point he had been to MIT and had his fifteen minutes as a rocket scientist. Deep inside, he was a few-years-on version of the same kid who was always drawing boats in high school. Today he is the high priest of full-keel cruising boats that, in subtle ways, are creeping toward automation.

And Johnson is keen to crank up the pace.

“Someday,” he says, “you will be able to step aboard a sailboat and turn it on, and it will sail itself. The world of electronics is working toward integrating GPS, radar, all the elements so that a boat can be made to take itself from waypoint to waypoint. ”

[In part one of this series we talked with Mark Ott at Harbor Wing Technologies which has done just that]

“With a motorboat, it’s almost easy,” Johnson says. “With a sailboat you need an integrated system for the rig. For a few years now, certain people on the other side of the Atlantic have been working on doing this for the disabled, and we’ve been working with them. It’s not a “program” per se. These folks have done one boat for a young guy in Denmark who became a paraplegic after a spinal injury. He has to control the boat with a breathing tube, but the man has a functioning 30-footer.

“There’s a red zone [hitting other boats, going into irons] that the boat has to be able to avoid, and otherwise the boat will sail itself. Tack automatically. Gybe automatically. The people who made this happen are academics. They’re not into marketing, and this is not a product, much less optimized for VMG. What they came up with looks like a cross between an erector set and Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

“I think they’d do other one-offs, but they realize the end-game is to automate boats for the general market, and that is our focus. Our intention is to integrate their technology into a ‘popular market’ package to simplify and automate sailing.

“Not many people seem to have an interest in pursuing this, but to me it was immediately attractive. The software side is beyond me, but I can come up with the rest. If not for the stinking economy, one of these boats would be in the water already. I have a mockup on the floor. We’re sourcing the parts. Just tell me when the market will have some color in its cheeks.”

That leaves some important “how” questions on the table, and to those, Johnson replies: “It’s too early to get into a description of the mechanics. We’re still sorting out how to fully integrate all the mechanical/ electrical/hydraulic systems. I am willing to talk about it in general terms, and I’ve made no secret of our intentions to develop this concept for the market, but I don’t want to have a running dialog on our developmental engineering details as we look at different approaches that may or may not wind up in the finished product.”

Increments

Over the course of the conversation, Johnson touched on enough sub-topics that other takeaways are inevitable. For example:

Johnson went to Lewmar to develop a captive electric winch system for his SP Cruiser motorsailer, the first captive winch for a 41-foot boat. All previous captive winches—they trim in or trim out at the touch of a button—had been built for megayachts or exotic racers such as Speedboat.

“Lewmar was ready,” Johnson says. “They were just waiting for someone to ask.”

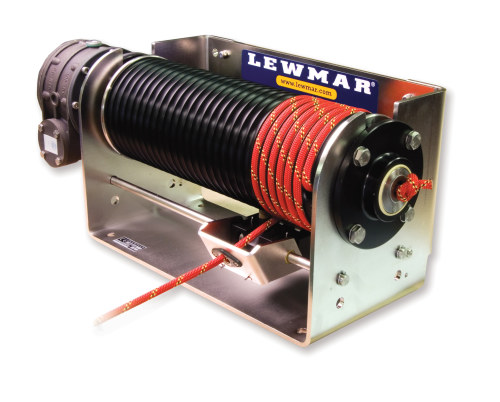

Lewmar now has two models, designated as 34 or 48 depending upon how many feet of line they can collect on their mandrels. At $5,500, the stow winch 48 is not cheap, but it suits the boat and the buyers. According to Lewmar’s Harcourt Schutz, it can crank in—or out—148 feet per minute at a maximum pull of 2,645 pounds.

And it’s not as though the Lewmar people themselves don’t understand a thing or two about marketing, as this pic, from lewmar.com, demonstrates.

“We haven’t built a new SP Cruiser without one, and we’ve retro-fitted others that were built before the stow winch came out,” Johnson says. We’ve been selling the winches at cost because they make the boats more appealing, and of course that’s a numbers game because the cost will come down as Lewmar sells more of them.

“The SP Cruiser is unapologetically a motorsailer,” Johnson says.

“Mo-tor-sa-il-er. Get over it.”

Hmm, if we’re talking motors, what about hybrid power? Electric motors?

“My dream,” Johnson says, “is a conformable battery that goes into the keel. Put the weight low. Right now, each battery is equivalent to a block of lead and every time we put one in I think, man, if only we could put this way down deep in the keel.”

Parting thoughts?

“There’s not a lot that’s really new. I visited a museum in Sweden where they had framing models—the shape was toothpick-thin hulls with rigs a fraction of the length of the hull—and those boats had roller furlers. They were from the 1920s.”

‘Nuff said.