Changing Dreams in Midstream

The sailing ventures of Dave Honey and Dick Honey

Posted March 7, 2014 By Kimball Livingston

I have something in common with the brothers Honey. Separated by a generation, we never got published in the pages of Yachting Magazine.

Five minutes after the end of the Second World War, and even before they were discharged from the Navy, Dave and Dick were already knee-deep in plotting a getaway under sail, East Coast to West Coast of the Americas. I challenge you to imagine yourself as a young co-owner of a newly-purchased, old-school fishing schooner, walking into the deep woods of Nova Scotia in the company of friendly local fishermen until you come to the perfect black spruce and they look up, and they appraise, and they declare in a lilt that rolls on like the sea, something like, “Aye, that tree’s about right to make a proper new mainmast for your boat.”

I was introduced to the tale through Stan Honey (yes, that Stan), whose father, Dave, was lost to us in 2009. But Uncle Dick is still here, and clear, closing on ninety as I write this. Dick told me the story of the tree, aka the mast. But it was Stan who shared with me the correspondence between his father, Dave, and then-editor of Yachting Critchell Rimington as a publication date spooled on and on through the 1940s and ’50s and into oblivion. I had to grin.

And I guess I have a leg up. Yachting paid me a hundred bucks for the first story I ever sold. They never ran it. Yachting also gave me my first commission. They rejected the story, which later ran as a feature in SAIL and later still became the first chapter of a book, Sailing the Bay.

This isn’t written to crucify Yachting. I’m just a reporter. These things happened, years ago and umpteen iterations of that magazine ago, ahead of a succession of owners and editors. Millennials may find it news that, from its founding in 1907 and into the 1970s, Yachting stood (almost) alone. RIP The Rudder. In its heyday, Yachting had offices a short walk from the New York Yacht Club. With features, columns and news reports from the various regions—news that was a few months old, but that was state of the art—Yachting was the natural, aspirational target for a twenty-something Dave Honey offering an account of a voyage that, while not unique, was singular. Very few people, in 1946, went ocean voyaging. But nothing I get from reading the long-ago writings of Dave Honey, and nothing I get from talking now to Dick Honey, makes it seem that they regarded that voyage as anything other than essential.

My kind of people.

Now, this is not going to be an everything-fits-together story, much less a you-gotta-read-this-or-else kind of story. But it’s a thing of beauty: Young men fresh out of service, members of the greatest generation, if you must, delivered from the threat of war, determined to take a bite of the sailing life before they settled into what they assumed would be the inevitable, consuming obligations of work and family.

Looking for adventure, they went. And how many of us have ever had the varnish stripped by a relentless Tehuantepecker?

THE CORRESPONDENCE

Aspiring writers may take this history as heartening or not, to see that travail is spread widely. I tried scanning Dave Honey’s two-page letter, but starting from mimeograph (you could look it up) it makes a difficult read. Below is a transcript. The original was written, I believe, from a business address. Note the dates.

July 23, 1959

621 South Hope Street Los Angeles 17, California

Mr. Critchell Rimington

Managing Editor

Yachting Magazine

205 East 42nd Street

New York 17, New York

Dear Mr. Rimington:

I have been going through some old files and came across a large sheaf of correspondence with you dating from June 7, 1948 and continuing through March 29, 1953. This file of correspondence, as you may remember, relates to the matter of my furnishing you with a series of articles and photographs. This series is still in your files in original manuscript form as well as a collection of color slides.

At the risk of testing your patience, I will quote from several of your letters over this period.

June 11, 1948…”I feel certain that there are various phases of your cruise that would make the best sort of article for us.”

May 11, 1949…“We are still struggling to get caught up on our inventory with the result that every time I hear from you and others as to the exact date of an article I shudder. Seriously, however, we are making real progress, however slow, and I do hope to give you a definite date soon.”

June 10, 1950…“We hadn’t planned to use your piece for another couple of months so that if you get the pictures back to me within the next six weeks or so, it will be quite all right.”

January 12, 1951…“I am now making some long-range schedules for the next five or six issues and I certainly will not forget your script which is anything but forgotten.”

Now, I do not think that you can accuse me of being impatient with this whole matter, Mr. Rimington, and perhaps it has been that you do not want to hurt my feelings by returning the manuscript and pictures. Let me hasten to assure you that this whole thing occurred so far in the dim, distant past that this really should not be a major consideration. Perhaps I can interest some historical society in the articles.

Patiently yours, D.C. Honey

SETTING OUT ABOARD UTOPIA II

The dream, as Dave Honey would describe it, was ambitious, to find “a real bargain in a small, seaworthy boat” and take her to sea. The modest pot of money to make it happen would come from the discharge payments of four young men, fresh out of the U.S. Navy in 1946, a decade when yacht building had been halted and many existing pleasure boats had been taken by the military and used hard. Prices for the few good boats were high. With Dave closing in on his date of discharge, but still at sea in the Pacific, his brother Dick Honey and two other already-free veterans—thrown together either by college or the Navy, a mix of Oregon, California and Ohio natives—had followed the affordable-boat trail to the unbeaten pathways of West Dover, Nova Scotia.

West Dover, Nova Scotia © Harbor View Cottages

West Dover today remains a fishing community with a population hovering about 200, except in summer, when tourists swell that number considerably. In 1946, West Dover was even smaller and a mite harder to get to. The first paved road, and the post office, came later. Getting around often involved hitchhiking, where the good news was that folks were friendly and generous and kind enough to switch out of their opaque, Scot-influenced dialect when speaking to strangers. The bad news, there wasn’t much traffic.

Added to the Honeys of Portland, Oregon were Brian Dunne of Pasadena, California and Mace Hallock of Ohio. Each had a piece of the dream, and yes, at a time when the locals expected their working craft to have a service life of about ten years, there was this 35-foot schooner that was priced right, not used up and correct in many ways. It needed just a few things. A cabin for example.

Dick and Brian were Caltech-trained physicists. Dick would later spend time working for the Stanford Research Institute (as would his nephew, Dave’s son, Stan). Mace was a mechanical engineer. Dave was an industrial engineer and our journalist of reference here. Along with their book savvy, there was plenty of the rough and ready can-do spirit that had just won a war with duct tape and chewing gum. Sure, they could build a cabin, bunks, shelving, lockers. Get some new sails. Sure, they could replace rock ballast with 2,500 pounds of railroad iron and batten it into the bilges, but not until a six years’ accumulation of fish scales had been cleared. There was something about needing a new mainmast, too, but here was a real boat, as Dave put it:

“The old fisherman sat aft on the counter by the lantern, smoking, and he watched the young men with a half-amused, half-hopeful glint in his eye. He had grown fond of the Utopia II, pine over oak on nine-inch centers. She had reached out to the Banks with him for six seasons and had stood up to weather that had sent many of the larger boats scurrying for shelter. He wondered whether these young’uns would know a good boat when they saw it. They looked like they might.”

Nine hundred dollars Canadian sealed the deal. That was about half of the combined discharge cash, even with most of Dick’s discharge money intact, for example, because rather than buy train tickets he had first hitched home to Oregon from his discharge in Chicago, then hitched his way back across the country to the East Coast to launch the search for a boat. Now, Utopia II offered the promise of the dream. He and his buddies had first proposed a cruise, in one of Dick’s letters to Dave. Drafting his magazine piece, Dave put down the words, “and what better time to take such a trip. We were all relatively unattached, out of the Navy and through school. I wrote back telling Dick to count me in for sure, having become increasingly uneasy about following in the immediate future the prescribed pattern of ‘settling down.’ ”

About the mainmast, Dick says now, “I forget just what was wrong about the mast, but the locals took us out to the woods and showed us the tree that we needed, so we cut it down, and that was fairly early in the game, because we still needed to build the cabin. We trimmed the branches – there was a lot of time spent with a spoke shave – and left it to sit and dry as far as possible before we had to step it as a mast.”

The list of needs grew shorter and longer simultaneously, and the season closed in, but Dick Honey recalls today that Utopia II (the name came with the boat) was the one successful cruiser of the half dozen or so mustered in Mahone Bay that summer. Success meaning, Utopia II would make it all the way to St. Petersburg, Florida. Not that that was The End.

“United Sailmakers of Lunenberg completed a beautiful new suit of sails at the unbelievably low cost of a dollar a square yard,” Dave wrote. The four boat owners—officially yachtsmen now—worked fourteen- or sixteen-hour days, “and we returned each night to a camp in the nearby woods.”

“We were living on onions,” Dick relates, “because onions were the cheapest food we could find.”

When the cabin was rough-finished, they broke camp and moved aboard. Meanwhile, their fisher friends were advising them to “get out before the September gales start blowing.” That meant that it was time for the felled tree to become a mast, fully dried or not, Dick recalls, “and we hauled her down there and put her in. That’s really all there was to it.”

Thus, Utopia II became a complete yacht. That is, a boat to be used for pleasure, but of the most practical sort. Luxuries there were none, just stuff that made sense, and “stuffed” with supplies, spares and tools was the state belowdecks on August 23, 1946 as Utopia II bade farewell to Mahone Bay and opened to the broad Atlantic. “We had each been in the Navy,” Dave wrote, “but let me at this point dispel any illusion that we had learned all about the sea and boats in that organization. On the contrary, our combined sailing experience might be had by anyone in a few afternoons of leisurely sailing on a protected body of water. But experience was forthcoming in quantity.”

This narrative will fast-forward through the voyage down the Eastern Seaboard. It was a time when life rafts from mothballed warships could be found stacked and abandoned on the docks, yielding a treasure trove of emergency rations to be “liberated” for a hungry crew. Otherwise, there is much to say but little that is new or instructive about that first encounter with profound fog and near disaster, or the first big blow, or the occasional groundings and frequent motoring upon entering the Inland Waterway—though few of my readers will have experienced same with a “little unreliable two-cylinder, make-and-break engine of about ten horsepower” that had to be flywheel-cranked. The size and sophistication of the towns along the way, 1947 to now, would have been different, and you probably don’t need help with that. Dave noted the change in vegetation, from Virginia’s pine woods to the cypress swamps of the Carolinas: “We were often greeted by small, solemn barefoot boys, each trailing his relic of a shotgun, each with a bird dog nosing in the brush nearby. Winding down the canal was almost like taking a long walk in the woods, being, if possible, more beautiful.”

There would be a long stretch through protective, deep woods, with the banks mirrored in calm waters, only to break out into the open of a windswept bay and go screaming, rail down and bug-free, into the woods on the opposite side and then back to mirrored calm.

But every cruise has its disappointments: “I fished off and on all the way down,” Dave wrote, “through reputedly the best striped bass, channel bass and weakfish waters, without any luck.”

Then came Florida and a turn to the west across the vast shallows of Lake Okeechobee and into the St. Lucie Canal, with flamingoes and herons raising a ruckus. Our foursome marveled at the speed and subtlety of the alligators. Utopia II emerged on the Gulf Coast at Fort Myers and led on to an anchorage at St. Petersburg, still just a town in that day. No one could foresee the statewide boom that would follow, rather soon, the invention of air conditioning. None among our crew could see what was coming next for them, either. Some work, for sure. Dave and Mace took jobs on a charter yacht while Dick and Brian set back to work in earnest on Utopia II, taking time out to crew and win Class B in the St. Pete-Havana race aboard the sleek cutter, Den-E-Von.

Along the way, in the way of cruising, Utopia II had crossed and recrossed paths with fellow voyagers but especially with a larger, well-fitted schooner out of Boston named Kelpie. Bonds had been formed. And so it was that, while Utopia II and her crew of four contemplated how best to replenish the kitty and effect repairs before setting off into the great beyond of the Caribbean, “A letter arrived from Howard Springer, the owner of the schooner Kelpie, proposing that we sell Utopia II and join the Kelpie for its trip through the Bahamas and West Indies, the Panama Canal, and the west coast of Central America and Mexico to Southern California.”

Imagine the jolt.

The route would be the same, but.

All those plans. All those dreams. And yet, all those plans and all those dreams were a dollar short, and it was possible for our boys to sell their doughty little schooner right there in St. Petersburg for enough to cover all costs to date.

Did somebody say, cover all costs to date?

“And so ended the cruise of the Utopia II, perhaps a little sooner than we had thought. But we had set no destination for our cruise, for the reason that, when one sets a goal in that sort of game, he becomes so intent on it that he forgets what he came for—a good time—and that we’d had with Utopia II. The morning that we left her to a new owner, she was nodding and tugging impatiently at her bow line.”

Fairwell, Utopia II . . .

BELOW: Selections from the two-page bill from H.G. Stairs, broker and outfitter, West Dover, Nova Scotia

August 23, 1946 H.G. Stairs

10% commission on Utopia II 100.00

5 inch Wilcox compass 31.03

Chrome galley sink pump 8.25

60 lb galv. Kedge anchor 13.75

Wooden case barometer 7.75

14 telephone calls 1.55

50 ft ½ ” Galv Wire Rope 6 X 7 4.75

Nautical American Almanac .75

Total of entire list (not shown) $454.99

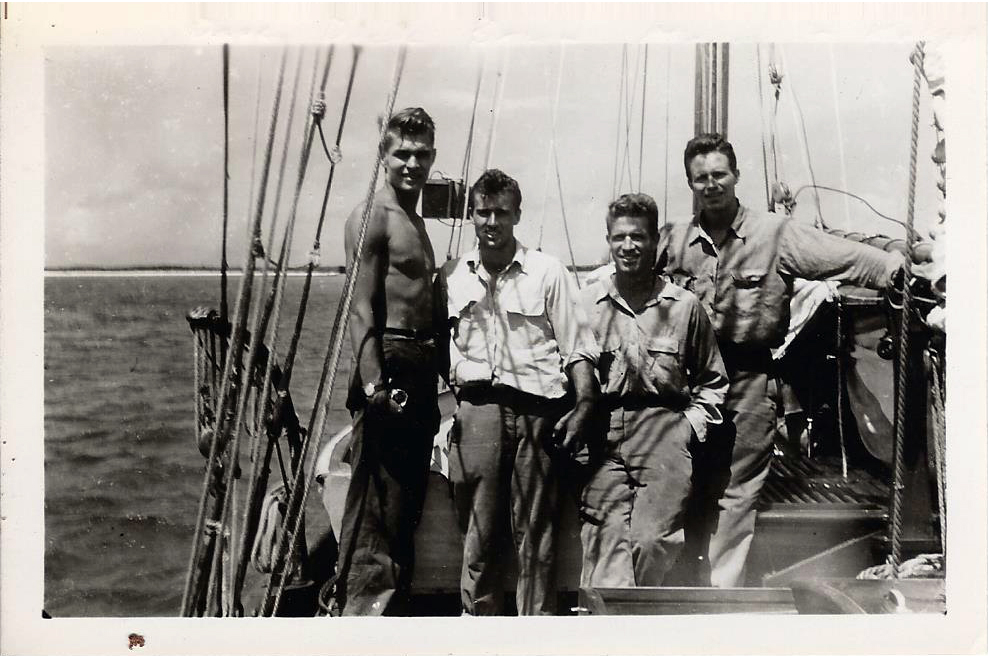

PART II, THE VOYAGE OF THE KELPIE

We open now on the east coast of Florida, where our heroes undertook the delivery to California of a finely-built, 79-foot schooner named Kelpie, pictured above. The schooner’s owner was detained at home by the demands of business, and that was exactly the sort of exigency that Dick Honey, Dave Honey and their companions were avoiding by taking control of their moment, by voyaging now, footloose and free. Free of war, first of all, and now even freer with their own rather demanding boat sold. Sold for enough to cover expenses to date, and with Kelpie’s owner covering expenses to come.

They had imagined going on in their own boat, and only through a mighty effort had they come this far. Now they chose to adjust, changing dreams in midstream.

On June 15, 1947. Kelpie cleared Miami, bound for a first stop in Nassau. Of his first encounter with the gleaming brightness of the Gulf Stream, Dave wrote, “The water changed to an indescribably beautiful shade of blue—a cross between robin’s egg and turquoise.” And there, right there, is another thing Dave and I have in common. My first experience of the Stream was a Miami-Nassau Race, and I looked at the water and wondered who turned the lights on down there.

In Nassau town, Dave observed locals balancing on their heads “everything from sewing machines to trays of nervous, clucking chickens.”

In a different generation, I missed that.

And then Kelpie sailed on.

Until jet travel, the islands of the Caribbean were a world or worlds apart, remote and exotic.

Kelpie’s crew would stop at only a few of those islands, but then would take their time about exploring. “We had no schedule,” Dave wrote, “We decided to stop when, where and for how long our fancies dictated—and a schedule would have been next to impossible to keep.” Our much-later survey will move fast-forward, so I will tell you that in the Caymans the boys took aboard an additional hand (who became a story later), and in Haiti they found a languid, idyllic air lost to later generations.

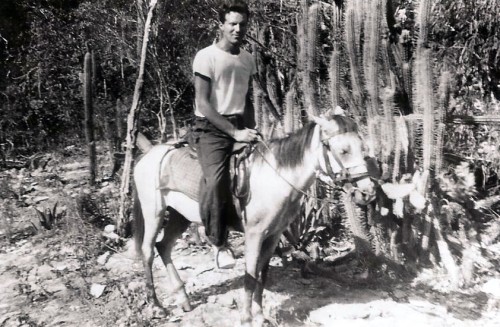

In Le Mole St. Nicolas, Haiti, they traded “empty bottles, tin cans, old clothes and bits of wire for oranges, limes, mangoes, avocados and a stalk of bananas, as well as the use of horses to explore the hinterland.” Horses that might look pint-sized to some eyes. There followed in Port au Prince adventures that Dave glossed over as “interesting voodoo ceremonies.”

Under way again, Kelpie took a licking in the Windward Passage and emerged with ripped sails and a leak. I’m pretty sure that in 2014 there would be no welcome for a random schooner seeking shelter in Guantanamo, but in 1947, for these ex-Navy boys, it was no trouble at all to arrange the services of a military travel lift, etcetera.

So the narrative goes, across the Caribbean, leading to a 600-mile leg to the Canal and through to the West Coast, where Kelpie stopped over in Balboa, Panama for yet more of the never-ending refurbishing.

Farther along, Kelpie stopped in the Costa Rican banana port of Quepos. There the crew was warmly received by Americans running the United Fruit Company base, and most of the crew took a small-plane flight to the capital city, San Jose, only to find that they had arrived in the midst of a revolt. The government newspaper offices were bombed overnight, the streets teemed with troops with fixed bayonets, and mobs roamed with sticks and stones and packs of yapping dogs. As revolutions go, it could have been a lot messier. Ducking into any nearest doorway provided adequate security, but, “interesting spectacle” though it was, two nights in San Jose was enough of that.

The return to Quepos revealed significant complications.

At this point, allow me to interject a quote from Hemingway: “Never trust a man whose story hangs together too well.”

I’ll interpret that to mean, never trust a story that hangs together too well. In his submission to Yachting Magazine, Dave related a highly-sanitized version of Kelpie’s time in Quepos. I heard a rather-different version as relayed by Dave’s son, Stan Honey. And I heard yet another version from Stan’s Uncle Dick, who lives about an hour north of the Golden Gate.

Here is Dick’s version, related while sitting at a dining table littered for the occasion with manuscripts, newspaper clippings and photos of that long-ago voyage:

“In Quepos the manager of the United Fruit plant befriended us. He let us shop at the company store, where prices were a pittance, and, well, everything was the same price.

“We found out that we could take a small plane up the mountain to the capital, San Jose, and that sounded like something we might never get a chance to do again, so Dave and I plus another American we had picked up in Panama took off for San Jose. We left our Cayman Islander, Boyce, in charge of the boat and [. . . events in the capital as described above] when we got back to Quepos, the dinghy was ashore, and Boyce was nowhere to be seen.”

Oops.

“Well, it turned out that Boyce was an alcoholic. We didn’t know it. He had come with good references. Physically, he was strong, and he had never touched a drop since coming aboard in the Caymans. But when we left Haiti, the priest there had given us a few bottles of, umm, sacramental wine, and when Boyce found himself alone on the boat, he lost his cool. And once he got going, the wine wasn’t enough. We also had a small arsenal that Mace had brought aboard, a German Luger with a big clip and a couple of 22s and a 32 automatic pistol, maybe more guns too, and when Boyce ran dry on the boat, he took the guns ashore and traded them for more liquor. But ‘smuggling’ guns into Costa Rica in the middle of a revolution was, you might imagine, a real big no-no. When we found Boyce, we found him in jail. Sobered up by that time. All he could do was hang his head in shame.

“And they weren’t going to let him out.”

What to do?

“Our friend at United Fruit made a persuasive suggestion: ‘You boys better get out of here before they confiscate the boat.’

“We went.

“Later, when we got to California, Dave tried to determine what had come of Boyce, but that was all those years ago, and we never did find out.”

Kelpie’s crew left Quepos aiming for Acapulco, some 1000 miles. First, however, they had to cross the Gulf of Tehuantepec, notorious for light airs interspersed with the fierce “Tehuantepecker” winds that blow from land to sea, funneling across the narrowest neck of the Mexican mainland. “Those are high-pressure winds,” Dick relates. “The pilot books are full of red flags, and they warn you to hug the beach and hug the lee.” The urge to keep moving in the light stuff, however, gradually lured Kelpie’s crew farther out to sea. Powering for mileage was not an option. Kelpie’s prop was mounted off center and shallow. Pitching in a seaway, it would air out with the risk over-revving the motor. “We never motored at sea,” Dick recalls, “except in a dire emergency.” That would come later. First came the storm.

Twenty days and 600 slow miles beyond Quepos, Dick wrote, “It came with a roar and no warning.”

“It” being a four-day Tehuantepecker that vacillated between Force 8 and Force 9, with gusts to Force 10. In Dick’s description, “We were down to a storm trysail and a reefed main. The skies stayed brilliant and clear day and night. The spray never stopped flying, never stopped accumulating salt and never stopped blowing the salt off. When it was over, all the varnish had been stripped.

“I wonder, do they still call it a Tehuantepecker?”

Yep.

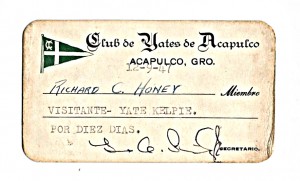

A month amid the comforts of the Acapulco Yacht Club resolved the varnish problems, one square inch at a time, and allowed for repairing other wear and tear before departing for San Diego, that welcoming sailor’s refuge under the lee of Point Loma.

By way of a stop at Socorro Island, tiny and yet the largest in the Revillagigedo Archipelago, about 250 miles southwest of Cabo san Lucas.

By way of breaking a fitting and losing the mainmast just a few hours after getting under way from Socorro.

By way of limping back to the island under power—now we’re talking emergency—and then taking a tow to San Diego behind a tuna boat that, by all odds, should have been nowhere near Socorro when Kelpie came limping in. Far from the mainland. On a remote island. With no radio capability.

And so it goes. Navigationis interruptus. And the source of many a tale to be told and retold and polished and repolished over the years. So Dick’s account of getting out of Quepos is a trifle (actually, more than a trifle) different from Dave’s unwritten tale, as told to Stan, of mysterious powders and strange sleep? The sands of time are forever shifting. Stan Honey says now, “I’m sure that listening to those stories as a kid had a lot to do with sparking my own interest in ocean sailing.” In which Stan Honey’s history is more than average.

And just to prove that the more things change, the more they stay the same, let me remind you that I opened with an account of Dave Honey’s years of correspondence with then-editor of Yachting Magazine Critchell Rimington, who never got around to running Dave’s story. To be precise, eleven years of correspondence.

It’s been a few months since I stumbled, again, across the box of letters, manuscripts and photographs that Stan placed in my hands when he first brought this up—the voyages of Utopia II and Kelpie—to see if there might be a story there for me. The package sat for . . . a while . . . waiting for me to find a way into the story, a way to tell it for the here and now.

As I aim to squeeze the Publish trigger in my software, the date is—

March 10, 2014.

Stan’s original note to me, along with that stuffed cardboard box, was dated—

December 19, 2004.

And Dick Honey turns 90 today.

Happy birthday, Dick. Hey there, JoAnne.

POSTCRIPT

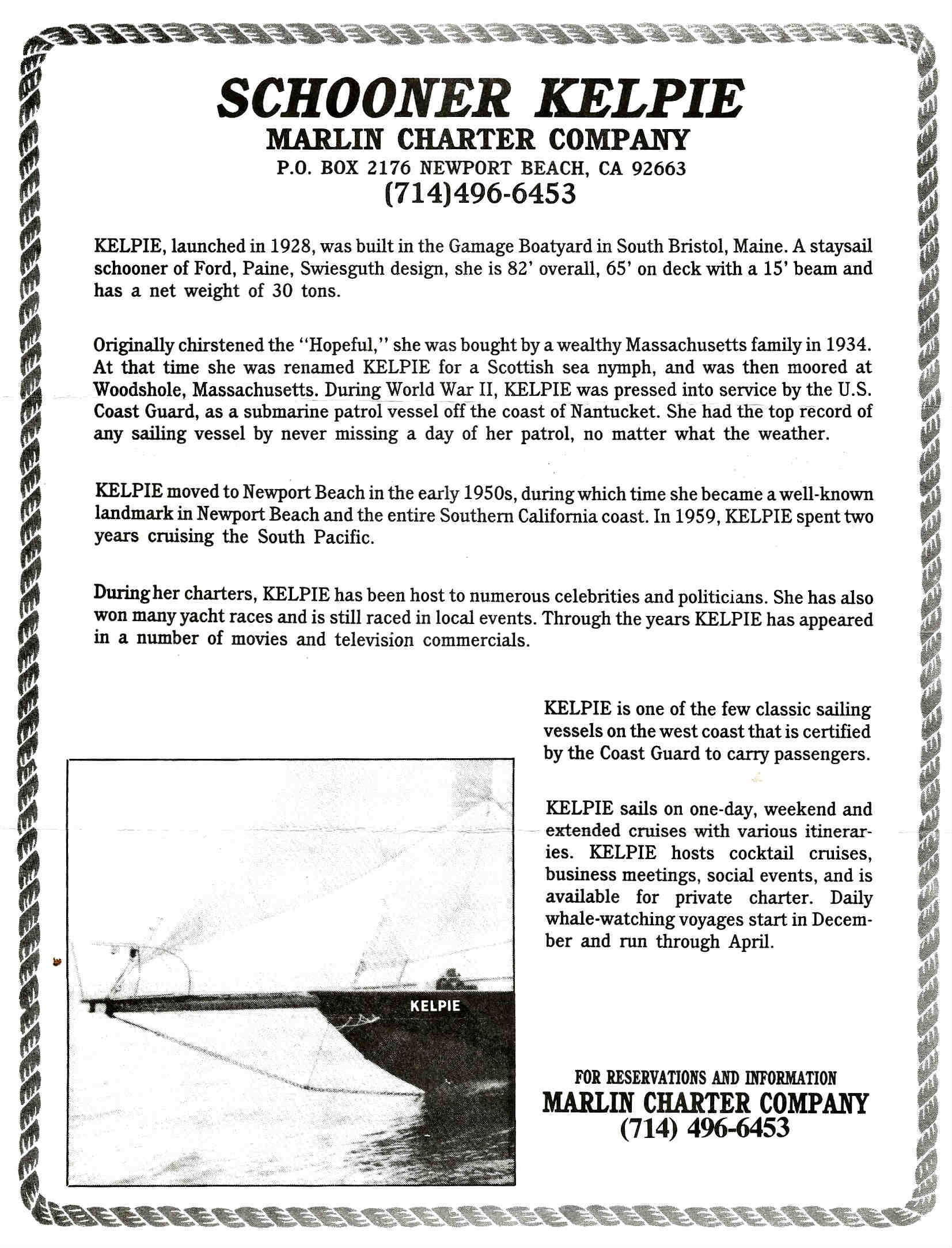

Kelpie was designed in 1928 by Francis Sweisguth, still celebrated for his most famous creation, the 22-foot Star. Kelpie had a long and storied sojourn on the West Coast of the Americas, including time in the charter trade out of Newport Harbor.

Kelpie was sold a few years ago into European ownership and the capable hands of Captain Charlie Wroe, well known as the captain of another classic schooner, Mariette, a boat kept like a prize jewel, which ought to give you a fix on this boat’s bright future. Wroe is giving Kelpie a deep-down restoration at the Gweek Quay Boatyard in Cornwall, U.K. under an updated name, Kelpie of Falmouth. Progress is easily followed through an open group on Facebook.

Wroe aims to have his “new” boat on the starting line for the fourth edition of the Pendennis Cup starting May 27. Meanwhile, the team is going deep. As of June, 2013, this was the look . . .

By February of 2014, it was more like this . . .

Insert Kelpie of Falmouth into this 2012 frame, and you have the look of the Pendennis Cup 2014. The future is looking good.