WIND: The First Twenty+ Years

More than 40 years ago, Dennis Conner’s comeback win at the America’s Cup in Australia inspired a Japanese movie producer to make a feature film about sailboat racing – WIND. Quite a few of the usual suspects of the sailing scene got involved, and I was one of them. Amid the fustigation, stress and associated smoke approaching America’s Cup 32 in Valencia, Spain, 2007, Craig Leweck of Sailing Scuttlebutt rang my chimes for a look-back. What follows is an update of that writing.

More than 40 years ago, Dennis Conner’s comeback win at the America’s Cup in Australia inspired a Japanese movie producer to make a feature film about sailboat racing – WIND. Quite a few of the usual suspects of the sailing scene got involved, and I was one of them. Amid the fustigation, stress and associated smoke approaching America’s Cup 32 in Valencia, Spain, 2007, Craig Leweck of Sailing Scuttlebutt rang my chimes for a look-back. What follows is an update of that writing.

Late in the production of the 1992 release, WIND, Peter Gilmour was steering a 12-Meter in the Indian Ocean off Fremantle Australia in just what the camera wanted, lots and lots of whitecaps and wind. Mind you, this wasn’t natural territory for a heavy old Cup campaigner that was being asked to fly a masthead spinnaker where no such thing had flown before.

But this 12-Meter was flying . . . The Whomper.

First assistant director Dean Jones hovered overhead in a helicopter with the cameras rolling. He was saying some equivalent of, “Looks good, guys, really good good good.”

(Break Break)

For those who came in late, here’s some background: Carroll Ballard was the director, and Francis Ford Coppola the executive producer, of the first film to give yacht racing feature treatment. Director of Photography John Toll went from WIND to “Legends of the Fall” and won an Oscar for that, then to “Braveheart” and won an Oscar for that, which should complete the case that the talents were extraordinary. But WIND never took off at the box office. Some people liked it, some didn’t, and lots of serious sailors walked out grousing that, yeah, maybe the sailing sequences got you going, but the story did not achieve the smell of authentic camel dung in high heat in the desert. Or, you know, something.

Over time, that washed away, and WIND found its place.

Carroll was firm that the Good Guys had to come from behind in the Big Moment to win the Big Race (no argument), and he was firm that the critical scene had to turn on something visual that anybody in the audience could see and understand. Why not a supersized masthead spinnaker on a fractional rig? And why not a sail sewed up special-like by tactician Kate (played by Jennifer Grey) pulled out of the bag in desperation on a rootin’ tootin’ screaming reach?

Thus “Gilly” on the helm, watching the waves while he steers but doing an awful lot of looking up, and not at the helicopter and Jones with his:

“Looking good. Really good good good.”

No, Gilly’s even more excited than that and his voice is up and he’s yelling:

It’s coming down! It’s coming down!”

“No, it looks good.”

The speedo touched 19 knots —

“It’s coming down.”

“Keep it up.”

“Not the sail. The mast. The F!#@ING MAST IS COMING DOWN!”

A beat.

(As they say in scriptwriting.)

And, well, it didn’t come down — the mast — but it’s lucky that Jones got enough footage to make the scene work. The backstay snapped and went flying, and only quick work on the part of the crew kept a stick in the boat, against great odds. I was not on the set, so any number of people might fine-tune this account, but that’s the gist of it. I’ve been hearing the stories long enough, having walked in as a technical consultant at an early meeting of producers Tom Luddy/Mata Yamamoto, director Ballard, and writer number two in a long chain of writers. That guy’s final, submitted script opened with a babe in a leopardskin bikini driving a cigarette boat on Narragansett Bay. The scene was never shot.

So here we are, many years downstream from the movie’s release, and more than several years from the first version of this account. My words in 2007:

I could declare, “The statute of limitations has run out,” but no, it’s an intriguing prospect.

I remember WIND.

It begins: I had met Zoetrope Studios producer Tom Luddy (if you know movies, you know he’s a hero) at a Cannes Film Festival, and I reckon that when Tom got a contract a few years later to do a sailing flick, I was the only sailor he knew.

By the time WIND was released, Tom Luddy knew lots of sailors, and I had gone from consultant to writer to consultant-to-editor to writer again, and it didn’t always fit like an old shoe. I recall tiptoeing into one early-morning script meeting, looking around, and asking, “Is anything all right?”

But these were Coppola’s people: dedicated professionals working very hard at things that never come easy, and I only got fired twice.

Excepting an auteur production, a movie is a strange beast, a bare-breasted collaboration. Seeing the movie now is like meeting a grownup child raised by strangers. I can pat myself on the back for insisting from the get-go that the movie had to have small boats in it, and sure, we could have a woman in a pivotal sailing role.

I had nothing to do with The Whomper. I even hated it. But later, when Paul Cayard and his EF Language guys racing around the world started calling one of their sails The Whomper, and as The Whomper became the wrinkle of the movie that gained a life of its own, I found myself thinking, doggies, I wish that was mine. Such a twisted form of immortality that would be.

Taking the temperature: Vincent Canby of the NY Times liked it, and International 14 sailors dig the movie because I-14s are players onscreen. There are plenty of fans, and the movie turned into a staple of rainy day junior programs. The scale runs all the way down to one guy I crewed for a bit, a big boat sailor from Southern California, the late Roy Disney, who called WIND, “Quite possibly the worst movie ever made.”

Or not, but this is truly a case of the blind man sampling the elephant. Not only was Gilmour there as sailing master, but other top sailors were there to sail the boats as actors.

Everybody has a story.

There was ample sailing and screen time for the likes of Bruce Epke (the Sheik onscreen and off), Stu Silvestri, and John Sangmeister, for example. Qualifications? Well, Sangmeister crewed for Dennis Conner in the 1987 and 1992 Cups and now owns Gladstone’s, a waterfront restaurant and sailors’ haunt in Long Beach, California. Epke and Silvestri were, among so many other things, some of Jack Sutphen’s famous mushrooms. It’s a good bet that Matthew Modine and Jennifer Grey have never forgotten that they really did sail an I-14 together in enough breeze to go medium-fast, briefly. Lisa Blackaller (Tom’s daughter) worked as assistant to the director and stood in for Jennifer as needed and was at least as cute.

I had the good fortune to be paired off writing with Roger Vaughan, whose book, The Grand Gesture, is only one of his many, but it’s my choice as the book about the culture of racing 12 Meters at Newport. Roger didn’t set out to teach history, rather to take you to places other sailing books do not. I don’t remember who I’m ripping off here, but one of the reviewers said something like, “It is a good book because the author is not part of the yachting establishment, and does not wish to be.”

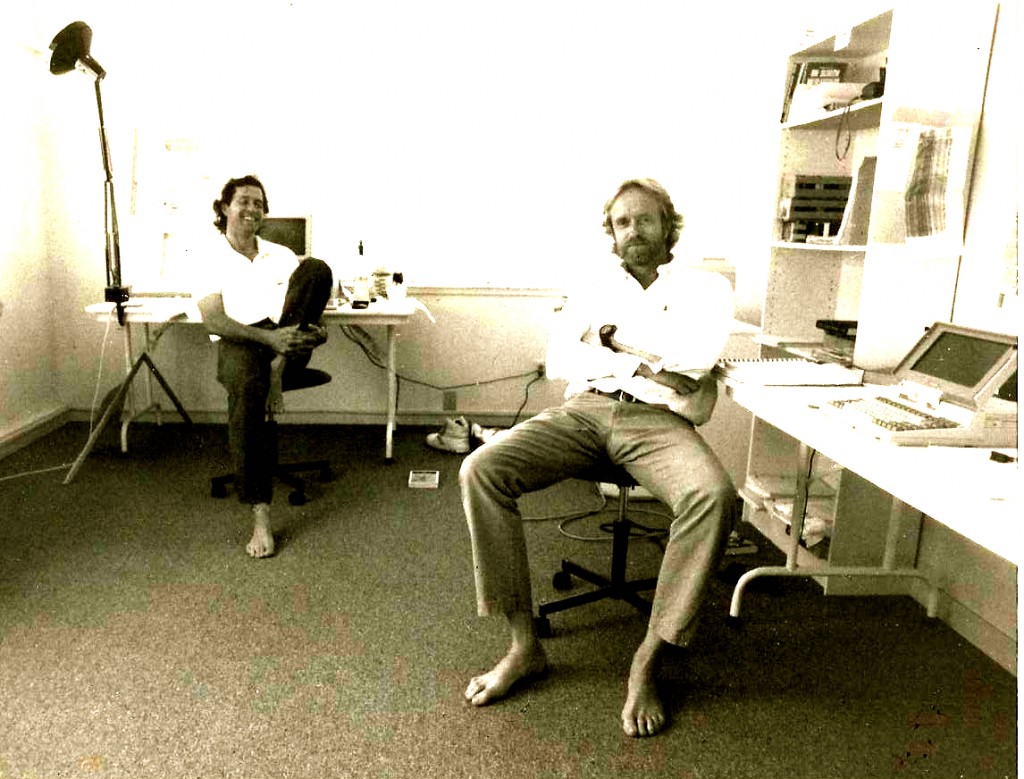

Here we see Mr. Vaughan, right, and companion, in the WIND offices across the street from Fantasy Studios, Berkeley.

The Newport world was very different from what America’s Cup competition has become. If you have a historical/sociological bent and you’re looking for a bit of contrast, or if you’re thinking of Newport as the good old days, you can find used copies of The Grand Gesture with only a bit of online searching.

Speaking of searching, let’s start looking for a bottom line here.

It’s a piece of work concocting a drama about the America’s Cup. You got your challenger eliminations structure, you got your history-as-baggage, but you don’t got your evil bad guy. Surely we’ve all seen at least one old racecar movie with a bad guy sabotaging the brakes on the good guy’s car, but you don’t want to go there.

WIND was driven by financing from Japan, which at the time was planning an America’s Cup challenge (co-producer Mata Yamamoto had co-produced Mishima with Tom Luddy, and Mata made this movie happen). Mata’s first move was to buy the screen rights to Dennis Conner’s post-Australia book, Comeback. The very first script opened with a scene of Dennis having breakfast —

I think I mentioned, many scripts were produced.

For those in the crew, the best times happened in the desert, shooting the scenes where the boat was supposedly under construction and they didn’t have to work a couple of 12-Meters every day in wind and waves. For me, the best times were early-on, when I was a consultant, and we’d go to dinner at Chez Panisse and I’d talk and people would take notes. Then they fired writer number two, and slotted me in behind him, which changed everything. My next meeting had an edge.

The surreal aspect came much later, in post-production on Sound Stage 29 (there is no Sound Stage 1 through 28) up a canyon behind Coppola’s house in the Napa Valley. I had been off the picture for a while, but here I was, called back in, and I was sitting on one side of a plywood wall, allegedly typing out scenes on a laptop, while Matthew and Jennifer on the other side of the wall were acting out reshoots of the “will you go with me or not” scene in a mockup of the cottage back in Newport.

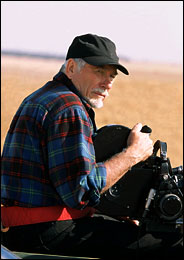

Where WIND succeeds, no argument, is in the editing. That’s true also of my favorite Carroll Ballard movie, Never Cry Wolf. And Carroll’s biggest hit (that’s Carroll on the right), The Black Stallion, is a brilliant example of a small story that allowed the filmmaker to discover the moon and stars glowing in a grain of sand. Having raised a horse-crazy daughter, I’ve seen The Black Stallion more often than any other movie, ever, and I’ve never tired of its lyric quality. When the race rounds the clubhouse turn and the camera truck driver punches the throttle and “the Black” surges to the front, I choke up. Every time. I just can’t help it. I think that’s called effective movie making.

Where WIND succeeds, no argument, is in the editing. That’s true also of my favorite Carroll Ballard movie, Never Cry Wolf. And Carroll’s biggest hit (that’s Carroll on the right), The Black Stallion, is a brilliant example of a small story that allowed the filmmaker to discover the moon and stars glowing in a grain of sand. Having raised a horse-crazy daughter, I’ve seen The Black Stallion more often than any other movie, ever, and I’ve never tired of its lyric quality. When the race rounds the clubhouse turn and the camera truck driver punches the throttle and “the Black” surges to the front, I choke up. Every time. I just can’t help it. I think that’s called effective movie making.

While the crew was shooting in Newport, Ballard told interviewer David Morgan:

“You can only make a film like that [the section of The Black Stallion shot on the island where horse and boy are marooned] when you spend a lot of time with a small crew. This picture has taken a lot of time but it’s mainly devoted to the mechanics of sailing and of getting the boats and the guys out on the water and getting the wind blowing enough to make it interesting, and then the thing with all the characters, a story that takes place on two different continents and all of that, the production is so huge that you know we’re not going to have time to do that kind of thing.

“It’s logistics and psychological dynamics and insurance, agents’ fees, stuff you have to deal with that explodes into the horror of the thing. In a way, the Matthew Modine character comes out naively, sort of the way I came onto films, that all you need is a camera and you get some guys, use the real small crew and you make personal stories. That’s how I came out of film school, thinking it would be possible, but it isn’t possible; it’s totally impossible. Essentially you’ve got to start with a successful con game to raise the money, and to get somebody sold on the project you’ve got to put together a package, and in order to do that you have to deal with a hundred different people who have their own interests – agents and the lawyers and the studio people, preparation people, dah de dah. And you’ve got to deal with the Teamsters and the fact that the lunch isn’t served on time and a billion other things that you can’t possibly imagine. Making a movie oftentimes takes a back seat to just moving the army from here to there.”

Ballard and Toll, shooting on deck with handheld, soundsynched cameras then newly-developed, captured the sailing footage for WIND. There’s no CG. Only a boat collision (a few seconds) is fake. And it was more than slightly handy to have the double wheels, so that Gilmour could steer off-camera while the actors did their thing opposite. Carroll was not/is not a racer, but he still sails the William Garden ketch that has been his baby for decades.

In the end, the people who had been in the movie business went on to the next movie, and the rest of us went back to doing what we do. But it was impossible in the moment not to enjoy the money and the company and the way that people think you’re important because you have a movie contract. I can’t tell you how to pull this off, but I can tell you that if you ever manage to take your wife to dinner at Trader Vic’s with a movie star who’s angling for a spot in your film, on a night when half a dozen of her girlfriends are in the room, you’ve got at least a six month window in which you can do no wrong.

.